George Woodman's convergence of flowers and mythology

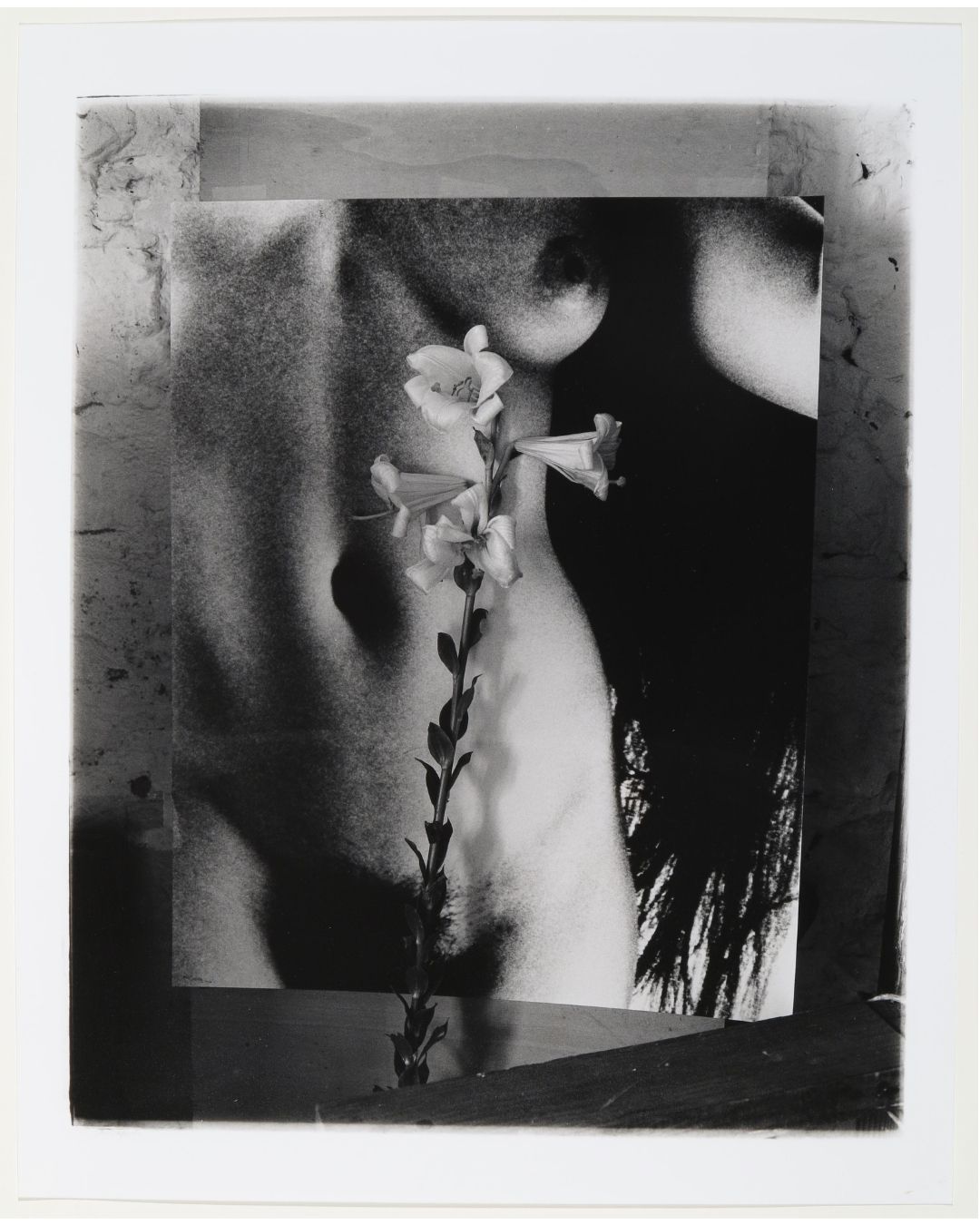

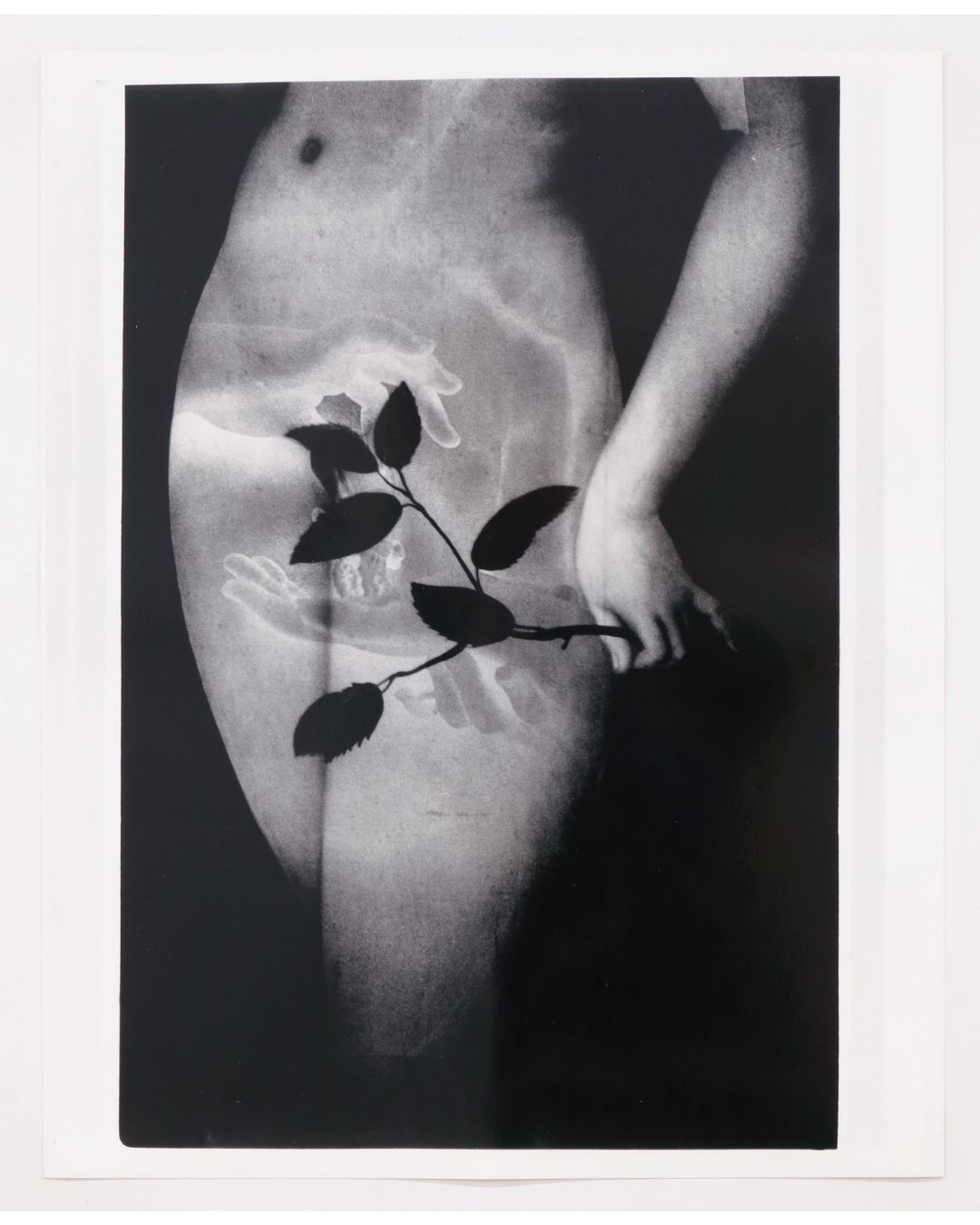

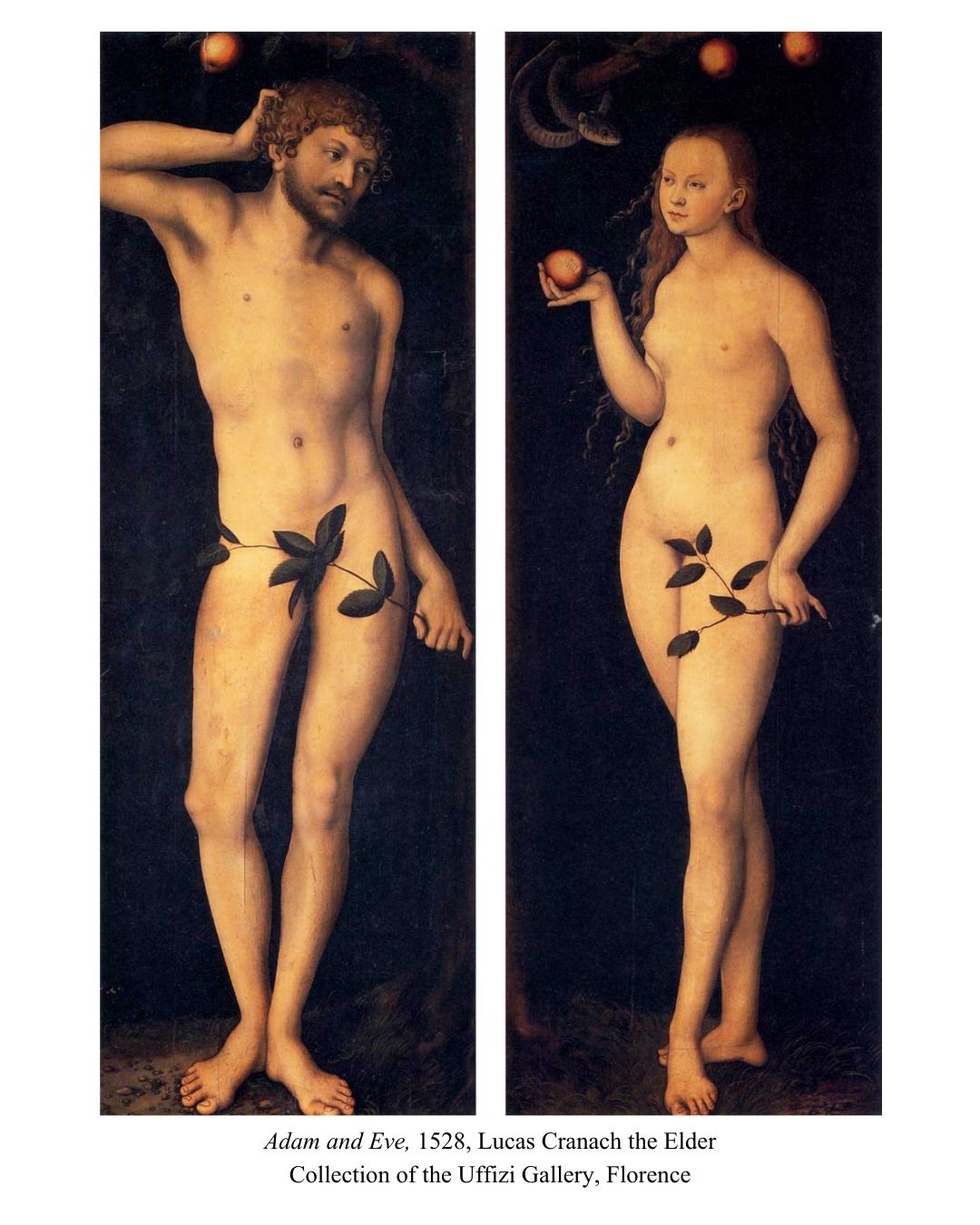

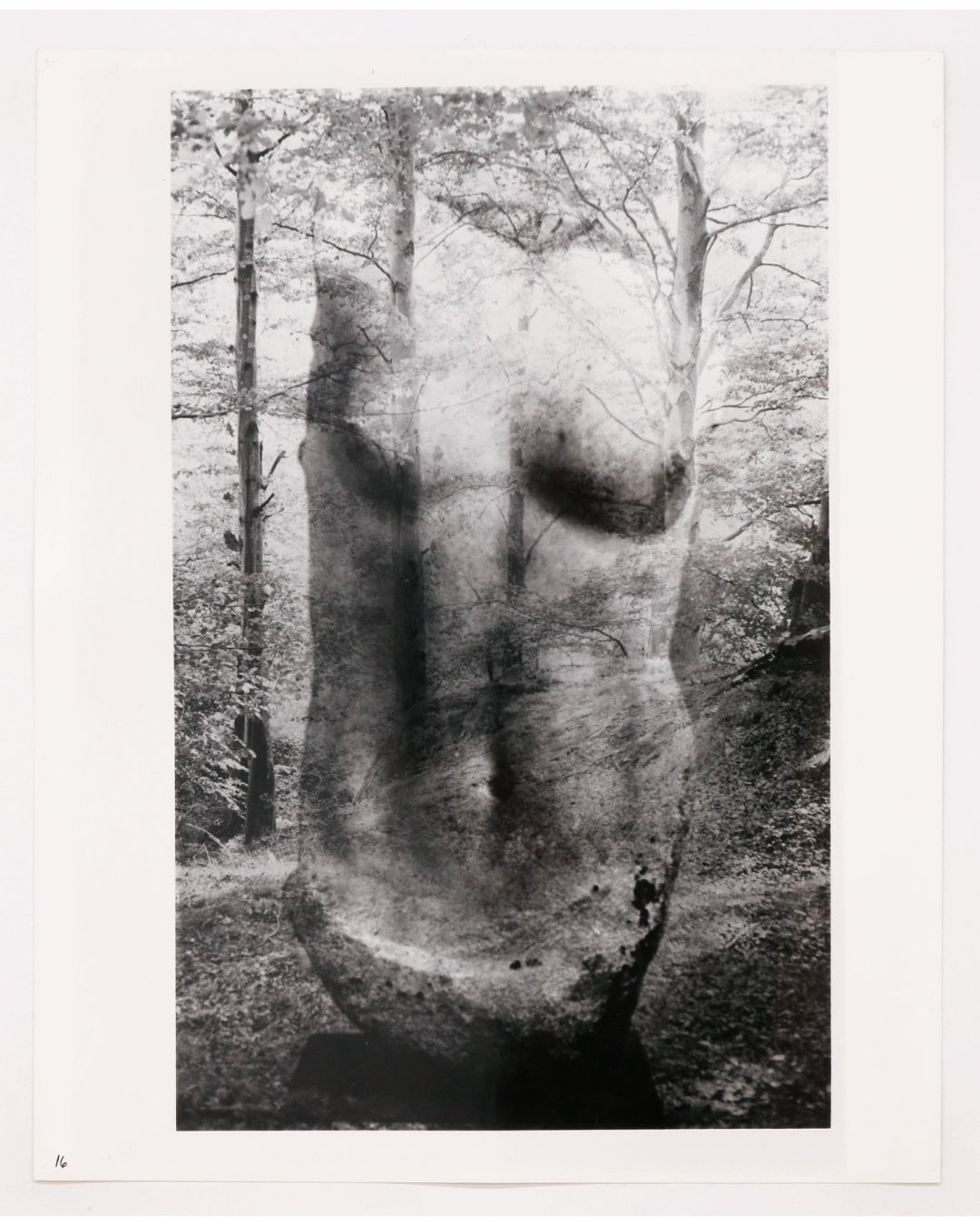

George Woodman’s sustained fascination with botanical motifs and his equally enduring dialogue with mythology shaped his practice for decades. While flowers have long served as symbolic devices across art history, Woodman used them in ways unmistakably his own: through pattern paintings built from floral repetition and, later, layered photographs where nature appears as still‑life elements or atmospheric, superimposed grounds. From Eurydice enveloped in a field of flowers and Daphne mid‑metamorphosis to Eve shielding herself with a fig branch and the lilies that herald Mary’s Annunciation, Woodman turns to flora as a conduit for mythic presence while adding his own contribution to the tradition he engages.

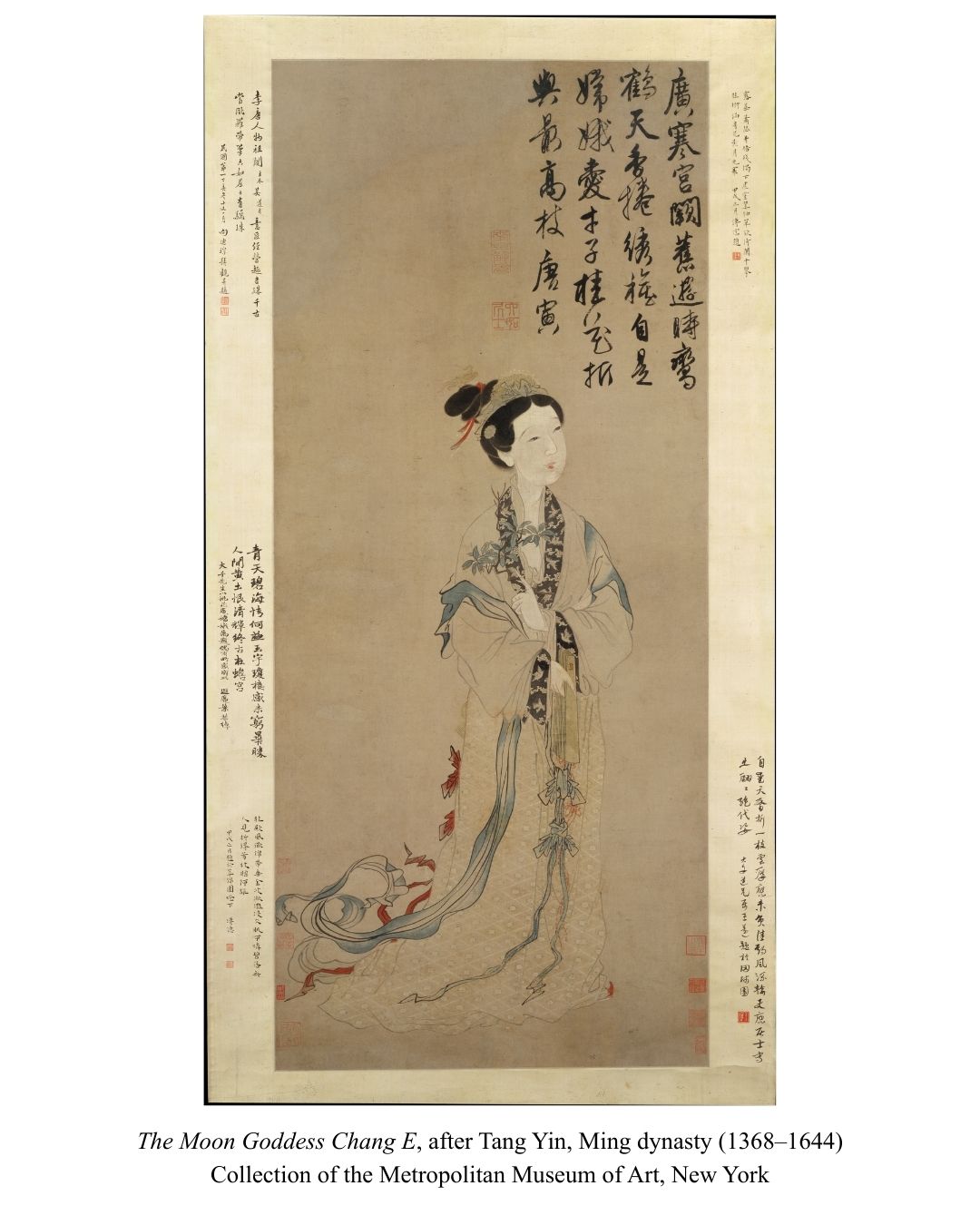

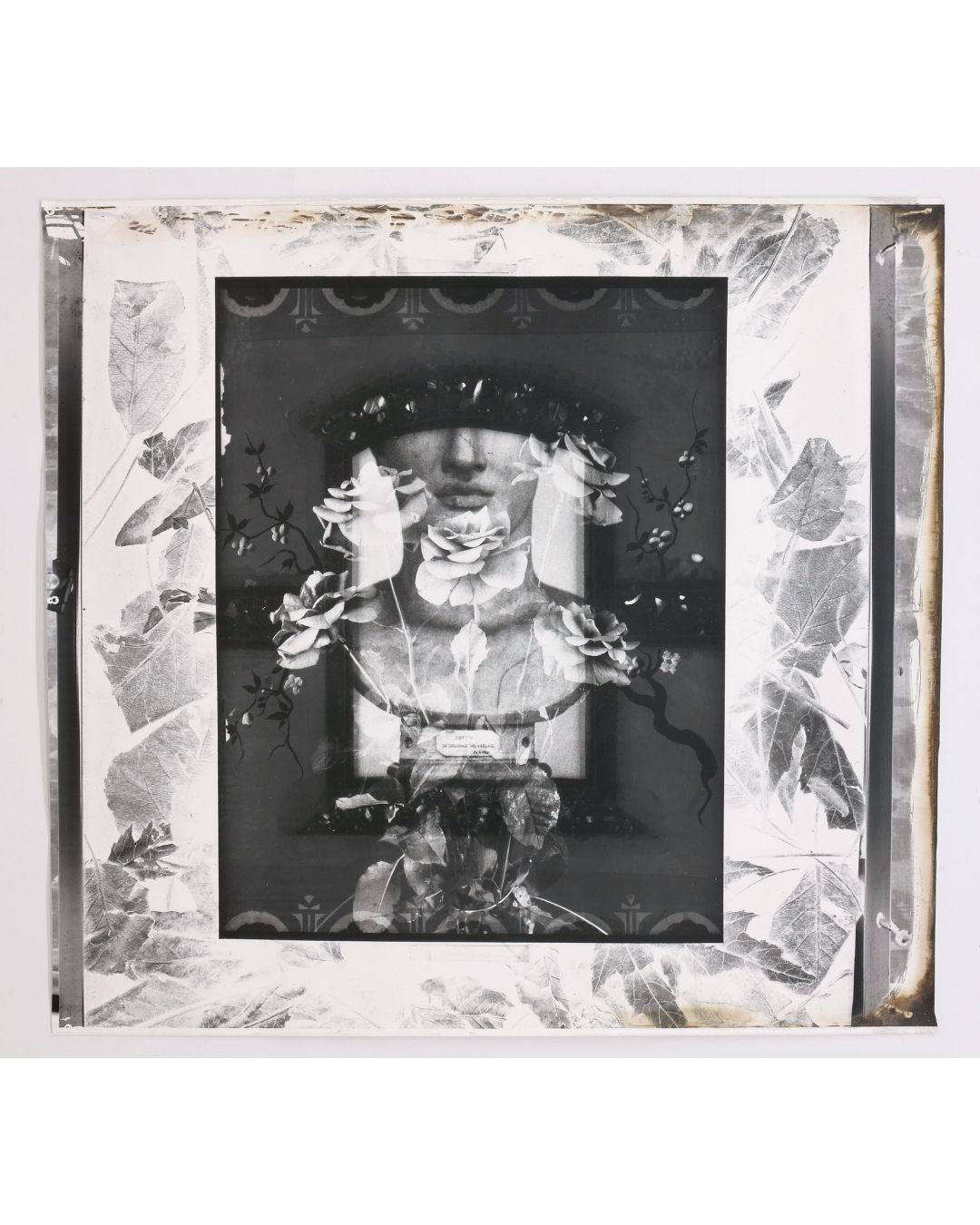

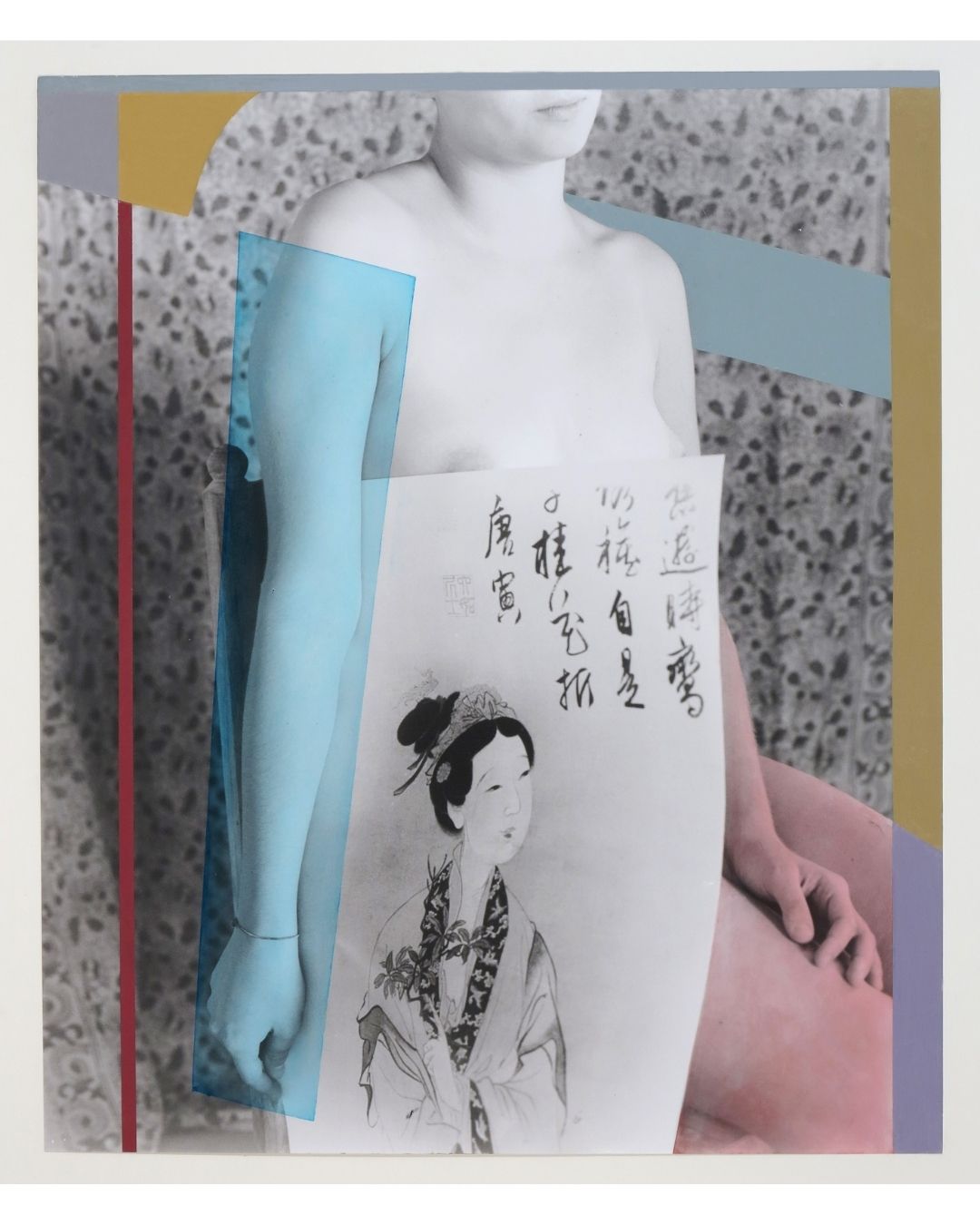

Blue Arm and Chinese Maiden extends this conversation through Woodman’s signature interweaving of distant geographies and temporalities. The central figure holds a rendered fragment of Moon Goddess Chang E by Tang Yin—a depiction that signals the goddess’s divinity not through lunar imagery but through a phoenix crown, crane collar, and a gui (cassia or osmanthus) branch, the latter a visual pun on “nobility” in Chinese. Woodman, a frequent visitor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where the work resides, may have first encountered it with his close friend Robert Harrist, Professor Emeritus of Chinese Art History at Columbia University. Behind the figure, a botanical backdrop unfurls; Woodman’s palette echoes the ochres of the original scroll and the celestial blues of Chang E’s shawl and gui.

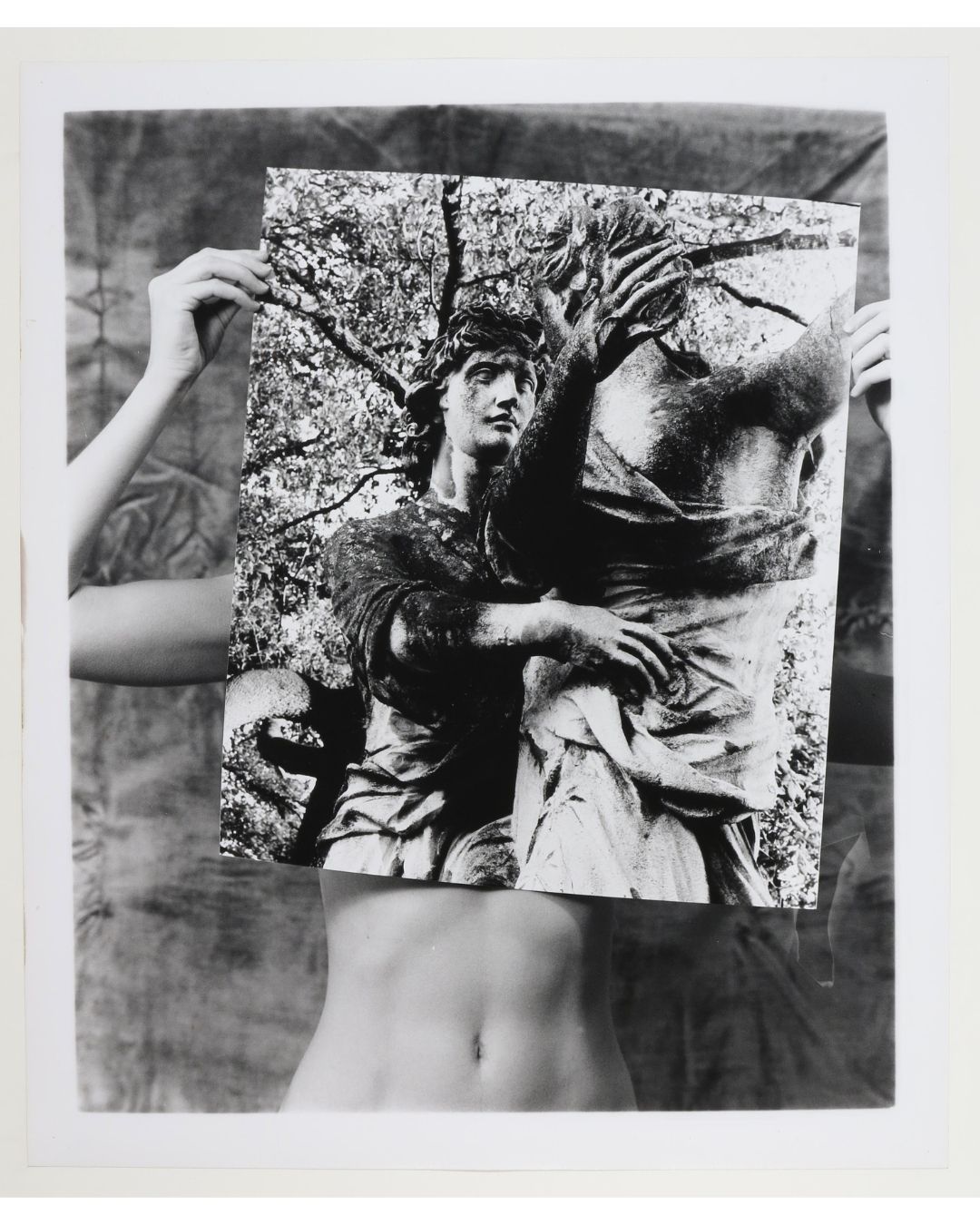

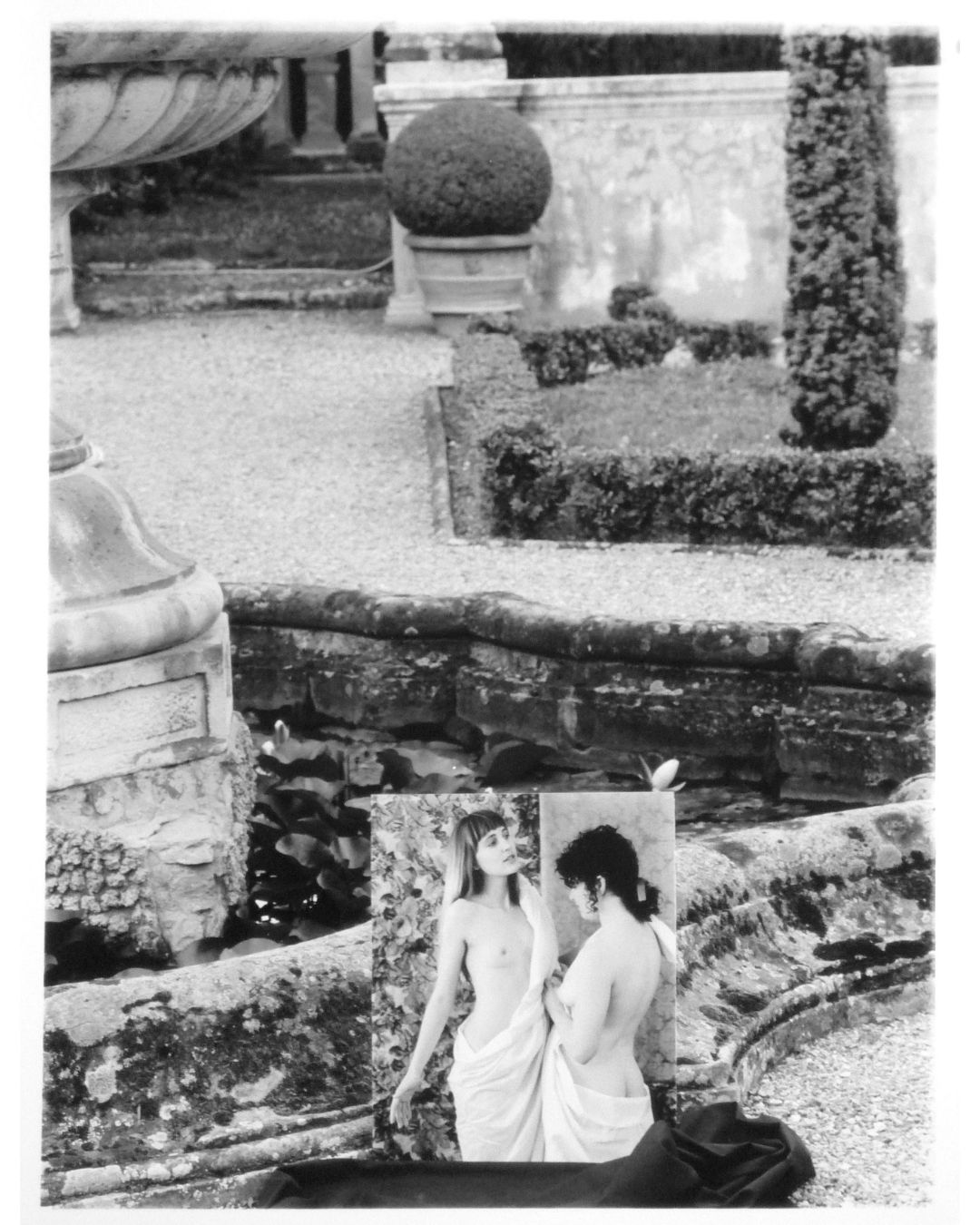

Woodman’s pictorial mise‑en‑scène—in which he superimposes images, sets contemporary ideals of beauty against classical ones, and presents female figures as “suspended, simultaneously within and third‑party to their representation, as in a hall of mirrors where one image refers to another”—underscores his ongoing dialogue with art history and its long tradition of artists who used the natural world symbolically. Through the contemporary medium of photography, where elements can be manipulated and the photograph’s supposed objectivity is continually questioned, Woodman reanimates historical iconography, inserting his own work into the lineage he both honors and transforms.