Essay

Re-Presentations of the Past: Through Francesca Woodman's Lens

By Ambar Vasquez-Mitra

Studio Institute Research Intern, Summer 2025

“I use nudes partely [sic]… in an ironic sense like classical painting nudes. I want my pictures to have a certain timeless personal but allegorical quality like they do in say Ingres history paintings but I like the rough edge that photography gives a nude. I like watching the immediacy of a photograph struggle with ‘timeless imagery’ …” (Francesca Woodman, Letter to Alberto Piovani June 29, 1979)¹

In a letter to editor Alberto Piovani, Francesca Woodman shares her desire for timelessness. Woodman highlights her focus on creating pieces that allude to and go beyond the source material that inspired her work. Referencing famous French neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, she cites the enduring nature of his works and the conversations that arise as a result of them. In her exploration of ‘timeless imagery’ and the tension created as a result of the nature of photography, her chosen medium, Woodman captures and revisits the history we thought we knew.

Throughout her career, Woodman reimagines classical motifs and repackages these ideas in contemporary contexts ultimately transforming the known image into a new story. Works such as Blueprint for a Temple (II) (1980), Untitled (1980), Untitled (c. 1977–78) and her artist books showcase a recurring relationship to antiquity, not as fixed point in time, but as ongoing conversations between source material and its reinterpretations through body, lens, and narrative.

Classical – Sculpture and Temple and Mythos

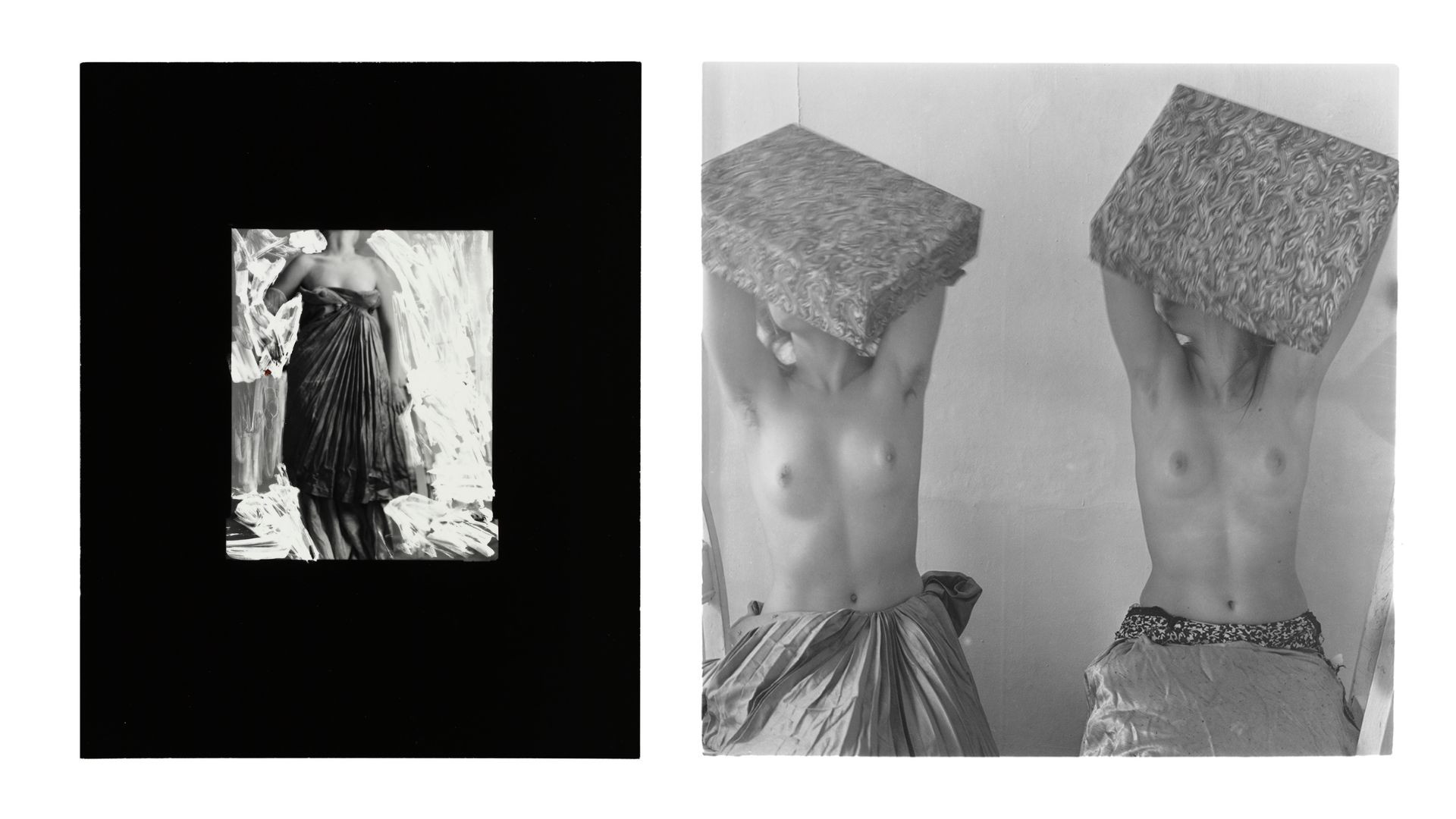

One of Woodman’s most prominent themes is her continuous reference to classical mythology and iconography. Some of her most striking pieces, Blueprint for a Temple (I) & (II) exhibit a fusion of classical themes and its modern counterpart that only Woodman could create. Combining the classical imagery of renowned Greek architectural forms with the modernity of decorative elements found in New York apartments, she creates an image beyond a Greek temple.

Her study of classical sculpture featured in the work, specifically the Caryatids and their subsequent representation using models and draped fabric, transformed the female body from background decorative ornamentation within these structures to the very pillars that sustain them. In doing so, Woodman not only presents a modern day spin on classical architecture and its purpose but calls into question and subverts the gendered imagery of classical sculpture.

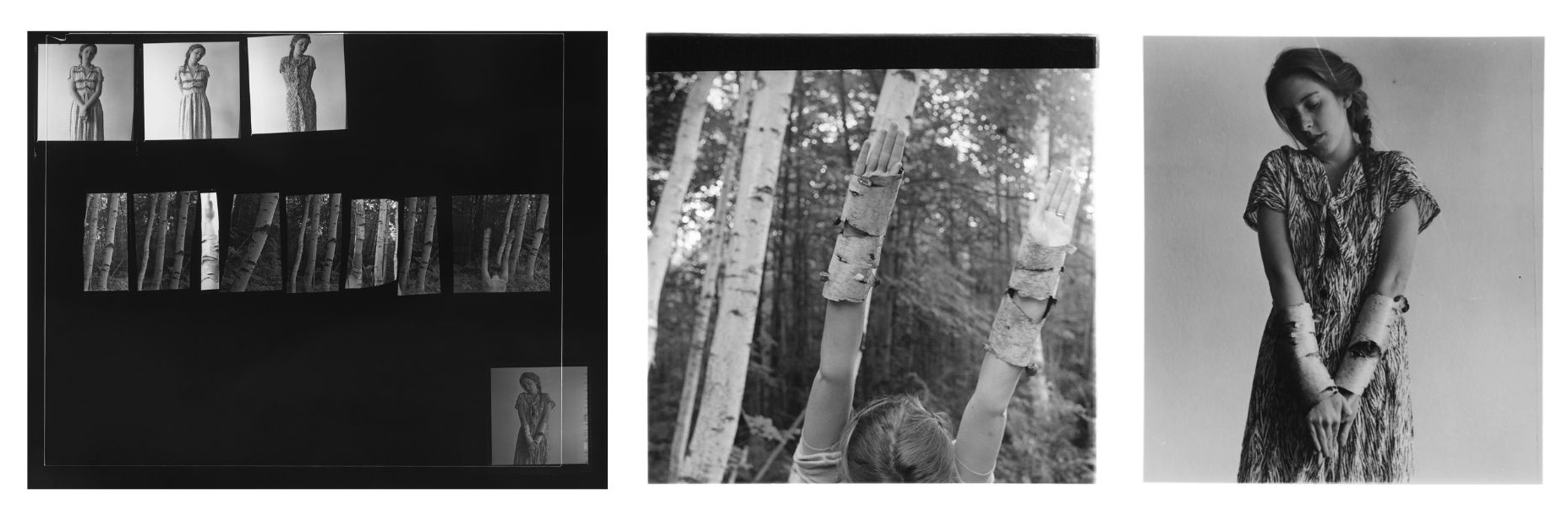

Woodman's relationship to the classical is similarly seen in earlier works, where she once again reinterprets classical mythos, through her reimagining of Daphne. Ovid's Metamorphoses portrays Daphne’s divine transformation as the tragic result of Apollo’s aggressive advances marking her loss of movement and bodily autonomy.

Her demise is depicted as follows:

But when she saw her breath was gone and strength began to fail, The color faded in her cheeks and, ginning for to quail, She lookèd to Peneus’s stream and said, ‘Now father dear, And if you streams have power of gods, then help your daughter here. O let the earth devour me quick on which I seem to fair, Or else this shape which is my harm by changing straight appair’ This piteous prayer scarce said, her sinews waxèd stark, And therewithal about her breasts did grow a tender bark. Her hair was turnèd into leaves, her arms in boughs did grow; Her feet that were erewhile so swift now rooted were as slow.²

Woodman, however, re-explores the myth and Daphne's role in the story we’ve all come to know. In this portrayal, Daphne the nymph takes center stage as the only figure in the image. Located in a forest, Woodman poses as Daphne herself mid-transformation as she becomes part of the surrounding landscape. Tree bark begins to encase her hands and arms, a reference to the metamorphosis of Daphne into a laurel tree as described by Ovid. It is here that Woodman challenges the proposed narrative, through her serial reworkings of Daphne—marked by repetition and variation—that actively resist fixed interpretations and destabilize the notion of a singular “real” image. This untitled series features a set of images in which Woodman (as Daphne) is presented repeatedly, always in motion, always transforming. In this depiction Daphne is reclaimed as an individual figure, uncapturable and exempt from the possessive nature of the other.

Historian and classics scholar Brooke Holmes further explains:

Woodman thus uses her photographic techniques to remake a classicized form that had been defined within its intermedial translation by abject fear and the need to escape from the female body as it is read perversely by Ovid as the cause of its own violation. Daphne is now set in a forest of mutable, hybrid figuration… Transposed from the ornate architecture of the museum back into the forest, the Daphne figure takes her place in a community much as the caryatids do in Blueprint for a Temple I and II.”³

Past & Present

“Although I spent a good part of my childhood in Italy it was not until 1977–78 when I spent a year in Rome as part of the European Honors program of Rhode Island School of Design that I tried to consciously explore through my art the counter balance of staid layers of Italy’s Art History and the Chaos of Religion, culture and politics today. The year in Rome spurred a whole train of works ranging from a series of notebooks of photographs playing on themes common to Italian Art History… (Francesca Woodman, 1980)”⁴

Throughout her time abroad and in the years afterward, Woodman’s photographs are marked by allusions to art history she’d encountered in Rome. In Untitled (c. 1977–78), she uses her hanging body to re-envision the crucifixion. Woodman is suspended from a wall in a home much in the same way a crucifix would be hanging within a domestic setting. Her body is posed and draped in a way that evokes strong connections to depictions of Christ on the cross clearly visible across Italian art tradition. Thus Woodman uses the crucifixion of Christ, an image decidedly marked by its representation of man, to re-create and center a woman as a reflection of the feminist discourse of the time.

_RH.jpg)

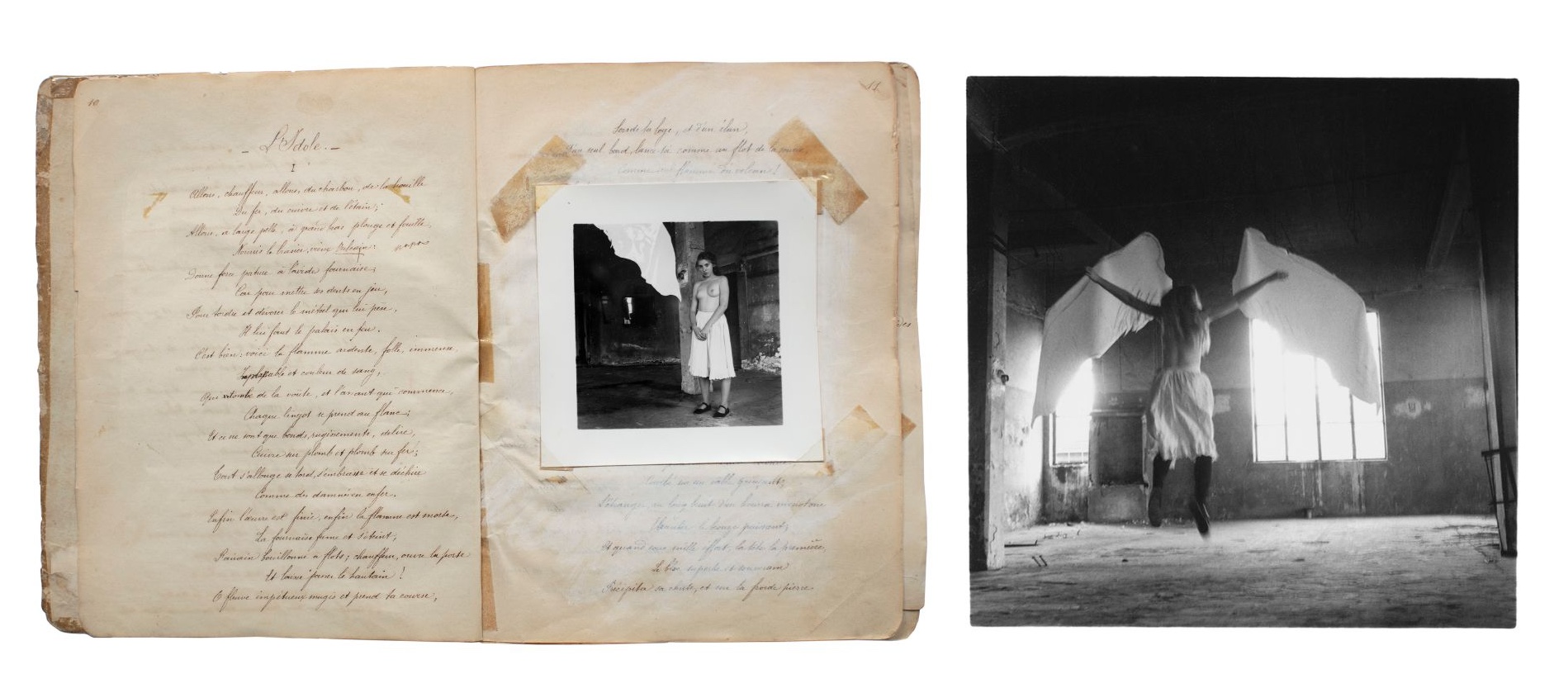

It was their reference to the past that appealed to her; the books showed traces of their former lives through elaborate cursive penmanship, colored ink, and careful calculations.⁵

Francesca Woodman's artists books illustrate the physical manifestation of her fusion of past and present. Using 19th century schoolbooks, ledgers, notebooks and handwritten diaries marked with Italian cursive, colored ink and various exercises, she overlays and inserts her images transforming the original purpose of these books into part of the story she creates. The books’ existing characteristics intentionally amplify her imagery as central aspects of her visual storytelling. These written additions and notes from the previous century ultimately create a narrative beyond the one originally presented.

In Some Disordered Interior Geometries (1980), Woodman becomes part of the geometric theme displayed within. The spread titled “Almost a Square” features a faceless Woodman wrapped in a canvas material, identical to the fabric draped on the wall behind her, almost (but not quite) blending in completely. This photograph presents Woodman as one of the many shapes included in geometrical problem sets once assigned to scholars. As such, Woodman's use of existing imagery and its integration into her work and vice versa serves to enhance the stories and histories explored going beyond its intended use.

In Angels, Calendar Notebook (c. 1977–78), Woodman once again revisits pre-existing imagery in art history and reshapes it through her lens. The notebook features a spread from Woodman's famous Angels series, where she highlights the dialogue between her work and the classical figures she encountered while studying in Rome. These black and white images reference not only angel imagery, central to the Italian art tradition, but also suggest a connection to another winged figure in classical myth: Icarus.

The dialect between soaring and falling which resonates with the artist's exuberant temperament—does not descend from a turbid sense of being, rather it comes from the archetypal representation of one who bravely takes flight, and then crashes and burns because of his own recklessness. This is the classic story of Icarus who, moved by enthusiasm, dared, but dared too much and ventured beyond limits. He exceeded his human potential, and so he fell.⁶

The photographs place Woodman at the center of an unfolding story, one marked by the act of movement: soaring and the inevitable fall back down to Earth. Her clever use of white sheets of paper or fabric, as a representation of wings in the photographs, hints at the human ingenuity of Daedalus in creating wings out of feathers and wax that allowed for his and Icarus escape from imprisonment. The images capturing her (the protagonist) in motion, blurred and almost illegible, render her as an artistic depiction of risk and liberation, however fleeting. Like Icarus, she explores flight, in her own terms: timeless and free.

Like Icarus, the artists soared and preserved as far as she could. As a woman and an artist Francesca Woodman demonstrated the power of the artistic gesture, the determination required to create the courage necessary to expose herself and her work.⁷

Works Cited

Allmer, Patricia. Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism. Munich; New York: Prestel, 2009.

Holmes, Brooke. “On Parenthetical Receptions of the Classical: Intermediality, Nesting, and the Gender of the Universal (Twombly’s Achilles, Woodman’s Daphne).” Parentheses of Reception, edited by John T. Hamilton, Evina Sistakou and Martin Vöhler. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2025, 425-456.

Keaney, Magdalene. Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In. London: National Portrait Gallery, 2024.

Kraus, Chris. Francesca Woodman: Alternate Stories. New York: Marian Goodman Gallery, 2021.

Pedicini, Isabella. Francesca Woodman: The Roman Years Between Flesh and Film. Rome: Contrasto, 2012.

Raymond, Claire. Francesca Woodman’s Dark Gaze: The Diazotypes and Other Late Works. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Jerinic, Katarina, “Francesca Woodman’s Artist Books: A Primer in Poetry and Pictures.” Francesca Woodman: The Artist’s Books. London: MACK, 2023.

Endnotes

- ¹Francesca Woodman: Alternate Stories, 82.

- ²Ovid. Ovid's Metamorphoses. Translated by Arthur Golding, edited by Madeleine Forey. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- ³"On Parenthetical Receptions of the Classical: Intermediality, Nesting, and the Gender of the Universal," 442.

- ⁴Francesca Woodman: Alternate Stories, 65.

- ⁵“Francesca Woodman’s Artist Books: A Primer in Poetry and Pictures,” 410.

- ⁶Francesca Woodman: The Roman Years Between Flesh and Film, 97.

- ⁷Ibid.